Alexander Roitburd’s new exhibition at the Dymchuk Gallery in Kyiv is called “Imaginarium.”

Before us is a quite recognizable Roitburd with his “trademark” palette-knife texture and habitual narrativity, which neither falls into tautological baroque (like in the project Le Roi Soleil), nor into the linguistic echolalia of children’s scribbles (as in Roitburd Versus Caravaggio or the S(Z)urbaran Passions). In a sure, unhurried, painterly manner, the artist extensively recounts the strange and impossible.

“Imaginarium” is a celebration of the total collage. Twenty years ago the critic Vladimir Levashov wrote about Roitburd’s method:

“The artist compiles texts with such ease, that he’ll soon begin to create fellow unforgettable Frankensteins. The forces responsible for organizing his artistic worlds operate through shifting, multiplication and combination. The principle and result of these actions is collage. Today it is no longer possible to think of collage as merely one of many techniques utilized by the art of this century. Little by little it standing out from the traditional composition system, growing into the prevailing aesthetic principle. Pointillism was already a prototype of collage, then the Cubists revealed the wealth of its formal possibilities; it was an important component of Surrealism’s aesthetic strategy, and Pop Art laid collage like a web over the entire surrounding world. In the era of postmodernism, it facilitated the erasure of the boundary between history and the present, and then collage emerged as the primary mode of organizing cultural text. Today, in the era without a name, when cultural fictions create complexes of reality no less viable than those facilitated by the latest technology, the borders between illusion and reality have become completely indistinguishable<…> The new reality, constructed outside the limits of time, is nothing other than sur-reality; it lives like a permanently active collage. It is also nothing but a crucible of unceasing transmutations; it is only a conditional place where forms are subjected to the most bizarre reincarnational caprices.”

Here we can recall that one of Roitburd’s projects as a curator in the 1990s was called “Doctor Frankenstein’s Cabinet” – as if to confirm Levashov’s prediction. But the very name of Roitburd’s “Imaginarium” already refers us to the “cabinet” of another doctor – Doctor Parnassus, with his traveling illusion show, from Terry Gilliam’s film. “It is he, Doctor Parnassus. Old as time. More than 1000 years. He will widen your consciousness, give you a chance. Let the doctor play with your imagination, broaden your horizons.” Indeed, “this world is full of magic and spells for those who see differently.”

Terry Gilliam’s Doctor Parnassus makes a deal with the devil. Doctor Roitburd makes a deal with the search engine Google, which is inexhaustible, like Borges’s Library of Babel, “whose chance volumes are constantly in danger of changing into others and affirm, negate and confuse everything like a delirious divinity.” His “Imaginarium” stands on the comparison of the incomparable and the combination of the incompatible. It is a junkyard of culture, a flea market of discourses and visual fetishes. In “Roitburd’s operating room” (©M.Rashkovetsky) fantasy mixes with reality, trash with the classics, curios with fakes, the absurd with hallucination, kitsch with the phantoms of the subconscious; and at every juncture, the “ears” of the amazing computer program Photoshop, which significantly eases artists’ difficult labor, treacherously protrude…

Roitburd generates a “new heaven and new earth” out of random fragments, like a “patchwork” made of scraps(*). Just as the illusion of an object is born from the chaotic strokes of Roitburd’s palette knife, so an eclectic whole arises from the arbitrarily connected objects. The artist calls this “surrealist play with Legos.”

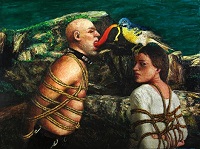

A new motif appears in Roitburd’s latest works – fantastical creatures, people with the heads of birds and animals. Their genealogy goes back to totem animals and further – to ancient Egyptian gods, monsters of antiquity and medieval chimeras. Considerably desacralized in the art of the Modern Age – from Chardin’s Monkey Painter to Max Ernst’s surrealist characters – “in the age of mechanical reproduction” they are ultimately driven out into the sphere of the profane – from glossy-advertising “creativity” to “doctored photos” on the Internet and Facebook avatars. The spiritualist seance of Ahasuerus, Haman and Esther reduces the territory of Rembrandt-Latour to trendy “kitty posts.” :)…

This entire bestiary poses submissively for us against a background of painted backdrops interspersed with a vintage BE-1 fan produced by the Comrade J.V. Stalin Kharkiv Electromechanical and Turbogenerator factory, an English porcelain plate “ACROPOLIS,” the automobile “ZIS-101” released in 1935 by the first state automobile plant, named after J.V. Stalin, a Chinese statue of a monkey climbing a tree, bone-handled cutlery, the planet Saturn hurtling at us in a locomotive with the same obtrusive totemic name “Joseph Stalin,” a cyclopean heart with a “crown of roses” – and it shows us the alternating figures of existential despair, serene contemplation, vulgar striptease, humble prayer, infernal eros, perverse BDSM practices and mystical self-absorption. The mise-en-scenes on Roitburd’s canvases are overtly staged; their space is not metaphysical, as in the Surrealists, nor is it psychedelic, as in the protagonists of the “New Leipzig School,” but it is theatrical, scenic, closed and dense.

Doctor Parnassus presumptuously made a wager with the devil, claiming that imagination is capable of transforming human life and filling it with meaning. Who won the bet? “As a prize – what I wanted more than anything – was eternal life or eternal suffering. He led me on, letting me win. He knew that times will change and that one day my stories would get old…”

Roitburd tries to avoid that trap. “I didn’t come to bring you sense, but nonsense.” The “Imaginarium”’s exhibits are packaged in second-hand “rented” names. This is also the artist’s device. What “Transportation is improving”? What other painting is there by Boris Nikolayevich Yakovlev from 1923, wood, oil, 100×140 cm? What, for heaven’s sake, about the AKhRR [Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia] and the idea of the socialist reconstruction of the Soviet land, pride in the young republic that defended its existence in the fire of civil war and is proceeding toward peaceful labor? The astute viewer, of course, will guess “what the artist wanted to say with his works”: train – “Hyundai”, train and lady – Anna Karenina, fruit – apple, part of the face – nose, Russian poet – Pushkin, oak – tree, deer – animal, chicken – not a bird, Ukraine – our homeland, death is inevitable. What sort of command, given by whom and to whom, which side is the other in relation to the west? Which rivers are called Babel, who has lost their virginity, to where has the Queen of Sheba sailed? Who is to blame, what is to be done, how to reorganize the Rabkrin [Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate], what are the joys of regency, what is the meaning of life and is there life on Mars? The artist dissembles, the artist knowingly obscures what wants clarification.

There is a legend about a Hasidic teacher who once interrupted his sermon and said to those listening, “My brothers, listen attentively to my words even if you don’t understand at all. For the day will come when the Messiah will arrive, and he will also speak to you, and you will also not understand. So you’d better get used to it.”

“Esther finished her story and a deep, oppressive silence reigned.”

(from an anonymous Internet term paper “Rembrant Harmenszoon van Rijn,” from www.zachetka.ru, 258 downloads, last download 24.10.2010; category – visual art, keywords: Rembrandt, artist, person, year, painting, portrait, life, hand, deep, entering, art, face, one, viewer, scholar. Rating ****

http://www.zachetka.ru/referat/preview.aspx?docid=3925&page=11).

Alexander Roitburd (about himself in the third person)

Kyiv, April 2013

___________________________

Once a Hasid was fasting between Saturdays. On the eve of the Sabbath, he felt such strong thirst that he nearly died. He went to the well and was ready to drink, but he thought that by not wanting to suffer just a little more until Saturday, he would forfeit the entire week’s fast. He overcame his urge, did not drink and left the well. And here he was overtaken by a feeling of pride that he resisted such temptation. But after thinking it all over, he then decided, “I’d better go and drink rather than let pride take hold of my heart.” And he went to the well. But as soon as he drew water, his thirst disappeared. On Saturday he went to his teacher’s home. At the moment he crossed the threshold, the rabbi called out to him, “Patchwork quilt!”